Pier 55: Pocket Gadget, Meme-tecture, or Something More Nefarious?

Courtesy Heatherwick Studio

My first column as architecture critic for Curbed.

Pier55 is a gadget. Pocket-size, stuffed with event spaces and paths to point you at the view, it will dangle off the southwestern edge of Manhattan like a Leatherman on a wallet chain. There’s a scenic overlook, a 200-seat amphitheater, a tunnel designed to give you an eyeful of designer Thomas Heatherwick’s signature mushroom piers, varied in height, holding up the molded surface of dirt, concrete and grass. Underneath the lawn, the plaza, and the pre-ruined staircases must be a theaters-worth of lights, wiring, speakers, electronics veiled in a skim-coat of plant life. As a design, Barry Diller and Diane von Furstenberg’s “$113 million dollar “gift” to New York City, is the culmination of two forces: private funding for public parks, with the High Line as reference point for elaborated outdoor urbanism, and architecture as online popularity contest, where good publicity is in direct relation to the amount of engineering required to make your park or your pool.

New Gig: Curbed Architecture Critic

Starting tomorrow, I will be writing a monthly architecture column for Curbed, serving as their first-ever staff architecture critic. I’m very excited to join a site I’ve been reading for what feels like forever, and to explore more ways to play architecture show-and-tell.

Read about the plans here.

Portfolio + Itinerary | Bay Area Modern

Last week was spring break, and my family flew out to San Francisco. We rented an apartment in the Marina, because I like the neighborhood’s proximity to Crissy Field and the waterfront, and spent the week exploring art, architecture and landscape. My goal was to pick locations that would be fun to explore for adults and kids: some design content, some outdoor experience, some interactivity. But for a visit to the De Young Museum that consisted only of a dash past the hall of Ruth Asawa sculptures and up the tower, we were all happy and got to see many things. (Coming from the East Coast, the beautiful weather certainly helped the mood.) What follows is our illustrated and annotated itinerary.

Day 1: Arrival, Crissy Field, Palace of Fine Arts. The area around the Palace of Fine Arts has been refurbished since the last time I visited, and there was a fair amount of wildlife to spot. Also nearby: a Richard Neutra house and lots of variations on two stories over a street front garage.

Day 2: The Presidio, the Walt Disney Family Museum, and Lucasfilm HQ. Even if you are anti-Disney, the WDFM is worth a visit: the emphasis is on the origins and early decades of Disney films. I find the process on display fascinating, as well as the concept art by people like Mary Blair and Eyvind Earle, always more elegant and suggestive than the finished product. The museum interiors, by Rockwell Group, are very theatrical, and feature some spectacular terrazzo floors. At Lucasfilm there’s the Yoda Fountain and a variety of memorabilia inside. I missed the exhibition on the planning for the new Presidio Parklands Project, designed by Field Operations.

Day 3: Alcatraz and the Embarcadero. We were there in time to catch the Ai Weiwei exhibit on Alcatraz, but I found the disused structures much more interesting. My 7yo loved the audio tour of the prison, complete with fake feet and daring escapes. After getting off the island, we walked down to the Ferry Building, bought lunch, and explored Embarcadero Center and the Hyatt Regency, both designed by John Portman (and others) in the 1980s. The glass elevators were like a theme park ride. Then we headed to Levi’s Plaza, designed by Lawrence Halprin, a highly playable combination of lawn, paved plaza, and fountain, screened from the road by a thick hedge.

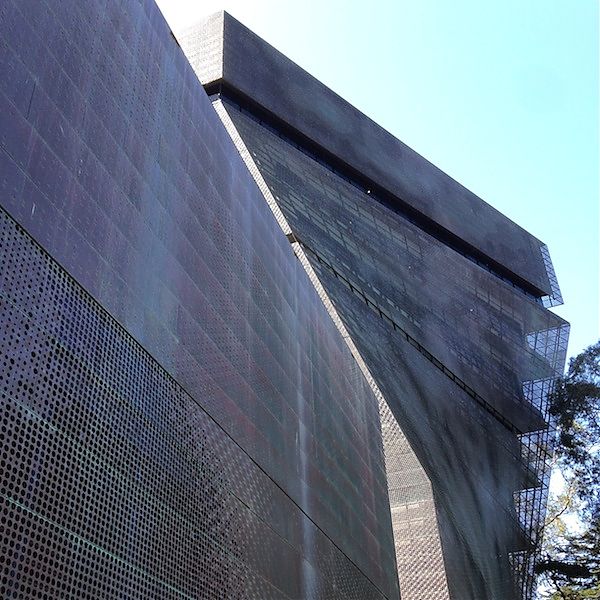

Day 4: Golden Gate Park, California Academy of Sciences, De Young Museum. Golden Gate Park has what they claim is the first purpose-built playground in America (though I think Boston might argue with that). Few elements remain, but the Children’s Playground is a big fun space, with one of the largest rope towers I’ve encountered, along with a climbable concrete wave. My children were not impressed by the green roof at Renzo Piano’s Academy of Sciences, but the Aquarium and Rain Forest were a big hit. Looking at the De Young from the Academy of Sciences, I have never been drawn to the building’s overall form. But up close, and from the tower, the skin and raked angles draw you in, as do the wedges of landscape. Why oh why is the lobby so formless, so vast, and so sheetrocked?

Day 5: Muir Woods, Marin County Civic Center. There are less frequented hikes on Mt. Tam, but Muir Woods was easy, short, and redwood-centric. Get there early and beware the poison oak. Marin County Civic Center is the best kind of architecture to explore. You can go pretty much everywhere in the building and there’s even a public cafeteria, with outdoor terrace and fountain, where you can eat lunch.

Day 6: Berkeley Hills, Oakland Museum of California. I have been a fan of the Cheese Board in Berkeley for over a decade so we went there first and then hiked up, up, up to see houses by Maybeck, Wurster and others. House peeping is definitely not a child-friendly activity. I had never been to the Oakland Museum, designed by Roche Dinkeloo at the same time as the Ford Foundation and one of their first independent commissions. It has many problems relating to the streets around it, but once you are inside its landscaped, public terraces unfold and it is a stunning experience. The lowest floor, devoted to science, is great for kids, as are the giant koi.

Day 7: A day of (relative) rest. Quick stop at Pietro Belluschi and Pier Luigi Nervi’s St. Mary’s Cathedral, glorious inside, a travertine hulk outside, and then south to Palo Alto. We walked through Ennead’s Anderson Collection at Stanford, finished last year. It has lovely galleries, very similar to those in Ennead’s Yale Art Gallery renovation. The central staircase is a dull waste of space, and the exterior is quite conservative. Stanford has to stop making its architects build tan. It’s obviously not going to help the Diller Scofidio + Renfro art department building under construction on an adjacent site.

Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building

The story of the $124 million Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood is a long architectural saga with an unexpected happy ending. In 2006, late Boston Mayor Thomas Menino first raised the idea of bringing Dudley Square, the historic center of the city’s African-American community, back to life by redeveloping the block that included the long-vacant Ferdinand Furniture building. Dutch firm Mecanoo and locally-based Sasaki Associates teamed up to enter a competition for the site two years later. The design—to create a centralized headquarters for Boston Public Schools (BPS)—had to satisfy two demanding communities: Roxbury residents and business owners and the 500 BPS employees being relocated there from sites across the city.

But it couldn’t be too expensive and, at least initially, it couldn’t be iconic: “Dudley Square has been the recipient of a lot of heroic urban design and planning ideas,” says Kairos Shen, director of planning for the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). “Francine [Houben, Hon. FAIA, the creative director of Mecanoo] and Sasaki won with a concept about what the square meant. This wasn’t an iconic autonomous building that you could immediately recognize—even though now you do.”

Letter to LACMA

On March 24 Los Angeles Times architecture Christopher Hawthorne hosted the fourth event in his Third Los Angeles Project, a set of public panels and talks looking at that city as it moves toward a new, more public-oriented phase in its development. This one looked at Peter Zumthor’s plans for a new Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

LACMA director Michael Govan, Los Angeles Times art and architecture writer Carolina Miranda, architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee and architecture critics Greg Goldin and Alan Hess will join Christopher Hawthorne to discuss the latest version of the Zumthor design, which now bends south to span Wilshire Boulevard. We’ll hear from out-of-town critics and put the LACMA redesign in the context of other museum expansions around the country. We’ll also talk about the legacy of William Pereira, architect of the 1965 LACMA buildings now on the chopping block, as well as how the corner of Wilshire and Fairfax and the Miracle Mile are poised to change as the museum rebuilds, the subway arrives and other nearby cultural institutions, including the Petersen Automotive Museum and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, pursue their own building projects.

Chris was nice enough to ask me to be that “out-of-town critics,” and I sent him the following letter, which was read as part of the panel discussion. After watching Michael Govan’s presentation on the plan, I would continue to stress questions about why the museum galleries need to be lifted up, how that benefits LACMA’s stated goal of increased transparency, and what exactly is happening on the ground and above your head at ground level. Govan kept calling that non-building space a “park” (because everyone loves parks) but I’m not sure that’s what it actually is. Also, I really regret not making it to Bruce Goff and Bart Prince’s Pavilion for Japanese Art on my visit.

Letter to LACMA

I’ve only been to LACMA one time. But this is what I did when I was there.

1. Took a photo (not a selfie) of Chris Burden’s Urban Light.

2. Signed up to see the James Turrell on an iPad at an outdoor kiosk.

3. Listened to the jazz band on the plaza.

4. Rode the escalator up and the elevator down inside what will soon be the old Broad.

5. Walked up and down the stairs and through Tony Smith’s Smoke.

6. Rapped on the enamel panels of the Art of Americas Wing.

7. Saw some art.

That motley list of movements and buildings and sights is, it seems to me, the essence of what LACMA is right now, a museum in many parts, a sum of choices, without hierarchy. A place where you can go in and you can go out at will, not when the architecture tells you to.

That’s an experience rare in large urban museums today, where the impulse always seems to be to agglomerate more real estate, connected indoors, around a central atrium or a central staircase. To go out you have to retrace your steps through long sequences of galleries, or pass to and fro past the store, café, coatcheck. There are many layers of architecture between you and the outside, however many slot-like windows the architect has inserted to tell you where you are. There’s a relentlessness to the arrangement that says, You should see it all, rather than, at LACMA, Why don’t you just pop in for a minute?

In fact, the only large museum I’ve been to that has a similar feeling, and was designed all at the same time, is Pedro Ramirez Vasquez’s Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. There, you can also go in and out easily, as each gallery has doors to its own garden as well as a central courtyard. A gap between two galleries becomes an outdoor display space, a level change leads to a shady café. You can skip stops, criss-cross, go up and down, sit by the fountain, and you always know where you are. The courtyard of the Anthropology Museum is shaded by a giant parasol, akin to OMA’s 2001 LACMA plan, which used a transparent roof to unite the parts without tearing so many of them down. [Ed. note: I realized last night I’ve had the details of this plan wrong in my mind for years, having reframed it as a greenhouse of the past and future.)

When I first read Peter Zumthor’s remarks about his plan for LACMA, it seemed like he got this. Liking small museums rather than large museums, creating a series of separate themed entrances to the collection, and pulling back the building to make room for outdoor activities, were all interpretations of the same motley path I followed. I thought the museum could create a tear-off ticket that would let you pay once and experience the museum over days or weeks, one leg at a time. But then I saw the blob or, I later decided to call it, the blot. It was still a giant totalizing figure, even though it looked different from the more mannerly toplit boxes elsewhere – even on other parts of the LACMA site. The fragmentary nature that seems part of LACMA’s DNA – it is #4 on the most Instagrammed museums list, even without a recognizable front door – seemed to disappear into the blackness. Would the LACMA selfie now include the museum as a dark cloud overhead?

Any architectural design has to win fans through suspension of disbelief. The model, the rendering, something has to make you believe that the architect can deliver the experience he or she has in mind. Zumthor’s LACMA hasn’t cleared that bar for me yet. We haven’t been given enough detail about how the parts would work together to knit together a possible experience, or even a good answer to the question: Why is this the best way to accomplish the museum’s goals? When it was a blot I wanted him to take the liquid metaphor further: A liquid should insinuate itself between solids (like the existing buildings) or soak in to the base layer, creating a new landscape. This did neither.

Nothing in his Zumthor’s previous museum work was similar enough to create a mental collage of how the blot might be to visit. The new version, released this week, comes a little closer to reality. What Zumthor seems to have done is embed galleries closer to his previous, petite museums in the inky form, eliminating many of the legs (too bad), and breaking it down into trapezoids as if to find a scale closer to his comfort zone. I’m worried about the circulation (once you go up, how to you get down, or outside?) and the underneath (is it like the underside of a highway?).

The ease of movement between inside and outside is gone once you raise it up on stilts to get over Wilshire Boulevard. And for an architect whose Swiss projects are embedded in the landscape, it seems strange to impose these flat black pancake floors around the galleries. Peter Zumthor is a critics’ darling because his buildings feel like special places and trust me, we’ve been to too many generic art spaces. What kind of place will this be?

Instagram's Endangered Ephemera

While most design objects need to shrink to fit onto the screen of your phone, postage stamps do not—nor do clothing labels, matchbooks, or machine badges. With car insignia, there is slight shrinkage; the same with vintage packaging. But a detail that you might have overlooked on an old object stands out when presented in the tight frame of Instagram. The offset, overlapping greens on a box of Greenbrier menthol mild pipe tobacco, for instance, or the forever-chic modernist trees on the Four Seasons’s long box of pink-tipped matches, created by Emil Anonucci.

These examples of tiny graphic-design ephemera are brought to our full attention in obsessive, single-serving Instagram accounts. This is not the Instagram of artistically arranged purse contents or filtered selfies but one that more closely resembles the olden days of Tumblr, when people, archives, and institutions realized that they could add their humble masterpieces into the digital image river that people look at every day.

Harvard Art Museums in 11 Tweets

Visited Harvard Art Museums last week. Thoughts on the new Piano building. 1. It was a mistake to fit that much program on that site…

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 2015… because it led to this bulgy boxy back end. pic.twitter.com/OO12UThVau

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20152. Talk about connection to residential nabe turn out to be bs, bec. Prescott door dark/uninviting and can't tell "clapboard" siding is wood

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20153. Court is very pretty and already being used by students. Needs more tables & chairs. And some scuro to the chiaro. pic.twitter.com/P3qwKduD5Q

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20154. Galleries are nice enough but those without windows are totally generic. Is this really what curators want? pic.twitter.com/pt5JNP1k2d

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20155. Most interesting spaces are where conservation/teaching happen. I loved seeing the big gallery curated for specific classes.

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20156. Pigment display, metalabharvard</a> interactive display of collection, conservation lab, all on top floor. <a href="http://t.co/nLxPJqkAw8">pic.twitter.com/nLxPJqkAw8</a></p>— Alexandra Lange (LangeAlexandra) March 16, 2015

7. I didn't understand the mix of periods/types of art floor to floor. Flow between galleries impeded by what felt like lots of glass doors.

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20158. This "identity." And that unhappy connection to the Carpenter Center. pic.twitter.com/gOdgxb1faN

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 20159. Rothkos "conserved" by light are fascinating, but become tech stunt rather than art for contemplation. Also clear they are site specific.

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 201510. So, it's fine, client is probably happy, but it lacks even some of the flourishes of Piano's Gardner addition. (I like the green.)

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) March 16, 2015New Wing at Corning Museum of Glass Invites the Light

Damon Winter / The New York Times

The first thing the architect Thomas Phifer did after being awarded the commission for the Corning Museum of Glass’s new 100,000-square-foot Contemporary Art + Design Wing here was to go back to his downtown Manhattan office and take an Alvar Aalto vase out on Varick Street. Aalto’s Savoy vase — the classic wedding gift for an architect — has thick glass walls that bend and curve, and a footprint that looks a little like a splotch. “It was a really sunny day, and as we looked at that vase in the light, it began to really glow,” Mr. Phifer said. “The more light you pushed into it, the more it glowed.”

Seeking Mr. Aalto’s timeless modernism, Mr. Phifer has been exploring the horizons of glass throughout his 18-year-old practice, exploiting its transparency, reflectivity and indeed the glow. He had been on the Corning museum’s radar since 2003 for his Taghkanic House, a visually delicate pavilion of light and white-painted steel fitting into an Arcadian landscape in the Hudson Valley, recalled Robert Cassetti, senior director for creative services and marketing at the museum. He also admired Mr. Phifer’s North Carolina Museum of Art, a series of aluminum-clad rectangles with 360 oval skylights cast in fiberglass. But could the architect conceive as stunning a plan for the world’s largest show house of contemporary glass art?

"Games that have withstood the fads of fashion and television should look like it"

I went online recently to buy my favourite board game: Othello. Or should I say re-buy? My grandmother still has the set on which I learned to play, stacked on a high shelf with Candyland and Hungry Ant, bingo, a baby animal memory game, and the little-known word-game Probe.

My family’s smaller travel set, a hinged green plastic box that flipped open, has been lost. Sold, perhaps, with our minivan, along with action figures stuck beneath the floor mats. Othello, with its baize gridded board, black-and-white pieces, Helvetica logo, and roll-top storage slots would seem to have timeless design. Mass-market yet elegant, each element had a purpose and all of these came together in a tidy package nice enough to leave out on the coffee table.

Of course, they’d messed it up. New Othello has a blue plastic board with curved, muscular edges, as if Old Othello had started drinking protein shakes. New Othello has shrunken chips and a board that flexes as you play. New Othello abandons the old, ominous-yet-exciting tagline “A minute to learn… a lifetime to master” for “Simple, fast-flipping fun!” New Othello sees itself in competition with sports. Old Othello didn’t have to beg for your attention.

Armi Alive!

A film about the life of Marimekko founder Armi Ratia? Sold.

In addition, the English Wikipedia entry for Ratia is just a stub. She would be a perfect person to write up during this weekend’s Wikipedia Edit-a-thon at the Museum of Modern Art.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness