The New Cooper Hewitt

Emoticon Carnegie Mansion mugs, Boym Partners

At a time when so many museums seem intent on new spaces for new design and new art (like the Whitney, Upper East Side deserter), it’s a relief that the Cooper Hewitt finally spent the time and the money to make their 1902 Carnegie Mansion sing. Rather than being a straightjacket, the mansion’s ornate rooms and halls now form a rich and idiosyncratic frame for design objects of all ages. Gluckman Mayner and Beyer Blinder Belle worked together on restoring, updating, and adding to the architecture. The cases, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, are crisp and clean, designed for sightlines and visual connections across the grand salons. The firm, as it did at Lincoln Center, has also jazzed up the outside: a new typographic canopy on Ninetieth Street leeeeans toward Fifth Avenue, and there’s L.E.D. lighting on the granite piers out front. Another example of new and old meeting in an elegant place is Boym Partners’ rendering of the mansion as emoticon: architecture transformed into “#”s, “+”s, and “[]”s, and applied to mugs, playing cards, and notebooks.

Fifth-Annual Year-End Awards

Five golden rings, four calling birds, three French hens, and two critics kvetching. What would the holidays season be without some lumps of coal? For the fifth consecutive year, prodigal contributing editors Alexandra Lange and Mark Lamster return to these robin’s egg blue pages to pick the best (and) worst of this year’s architecture and design. No middle fingers, we promise.

Jabba the Hut Award for Sensitive Urban Design: To George Lucas, for thinking he can dock that facocta Space Mountain on Chicago’s Lake Michigan. PS: Hey George, no design approvals until you release the original Star Wars on DVD without your “fixes.”

Most Unexpected Blobmeister: Peter Zumthor, whose hovering black form for LACMA continues to provoke headscratching.

Top Jargon of 2014: “tactical urbanism,” now enshrined in a MoMA exhibition, and close colleagues “pop-up urbanism” and “bottom-up urbanism.” We’re dangerously close to enshrining the small moves as we once did the big plans.

Best Architecture Money Can Buy Award: Tadao Ando’s new campus for the Clark Art Institute, a pristine if pricey exercise in museum building, with assists from Reed Hilderbrand and Annabelle Selldorf.

Most Architecture Money Can Buy Award: Frank Gehry does his thing in Paris, now with lots of glass.

Bringing Brutalism Back Award: David Adjaye’s Sugar Hill tower, in Harlem. A kinder, gentler brutalism.

Brutal Rejection of Brutalism Award: The Whitney departs its brooding, beautiful bastion by Marcel Breuer to hang out with Jean-Ralphio and his ilk in the Meatpacking District. Sigh.

First Brutalism, Best Brutalism Award: To Timothy Rohan’s long-in-the-writing (but couldn’t be more timely) The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. The rare monograph that leaves you wanting more—and we do wish there were more photos.

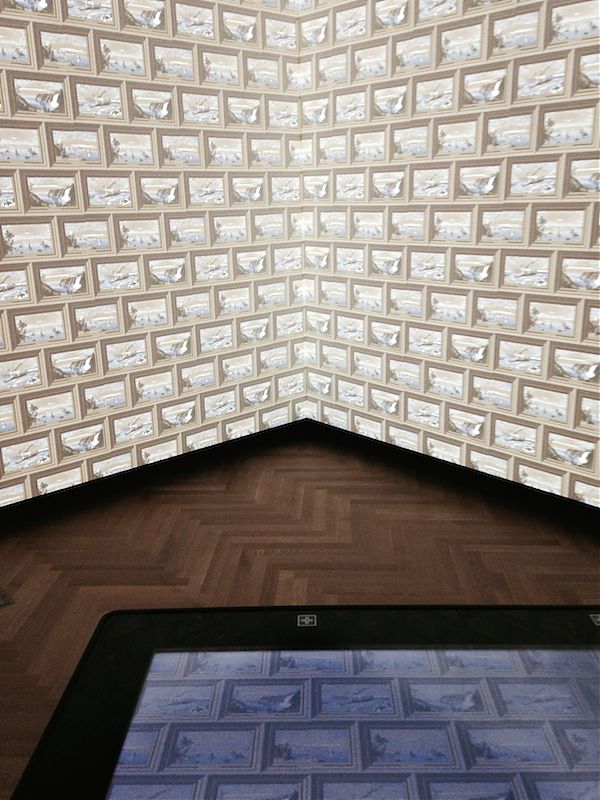

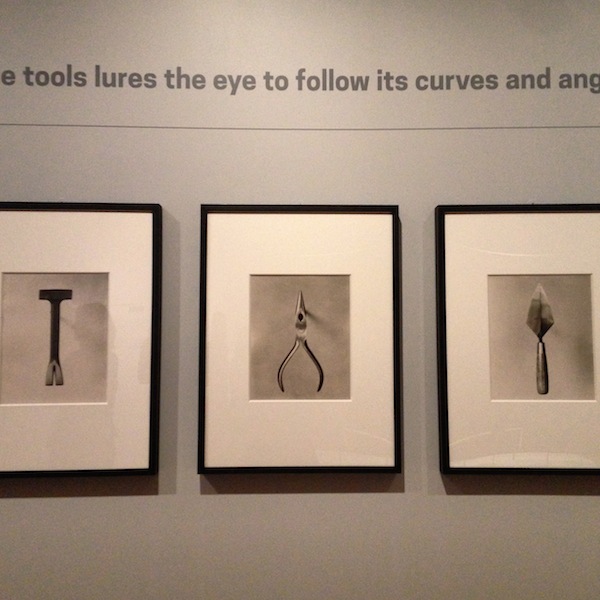

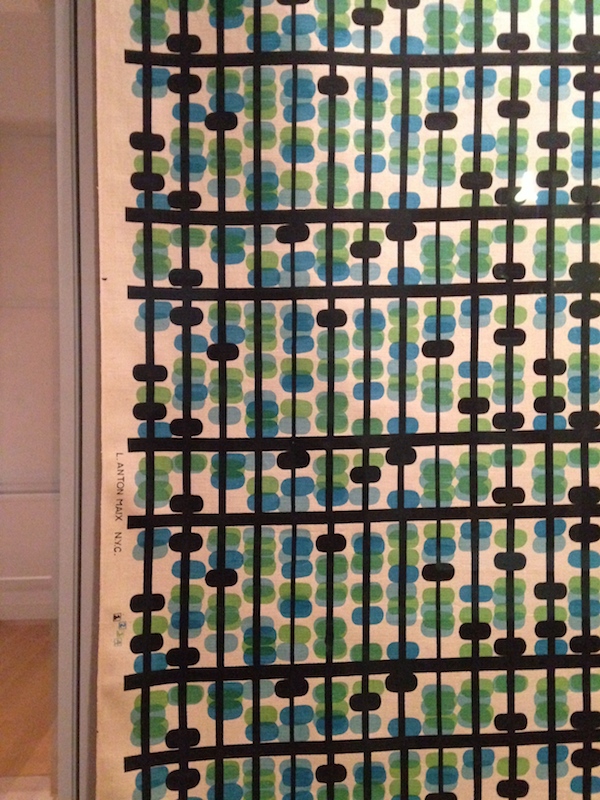

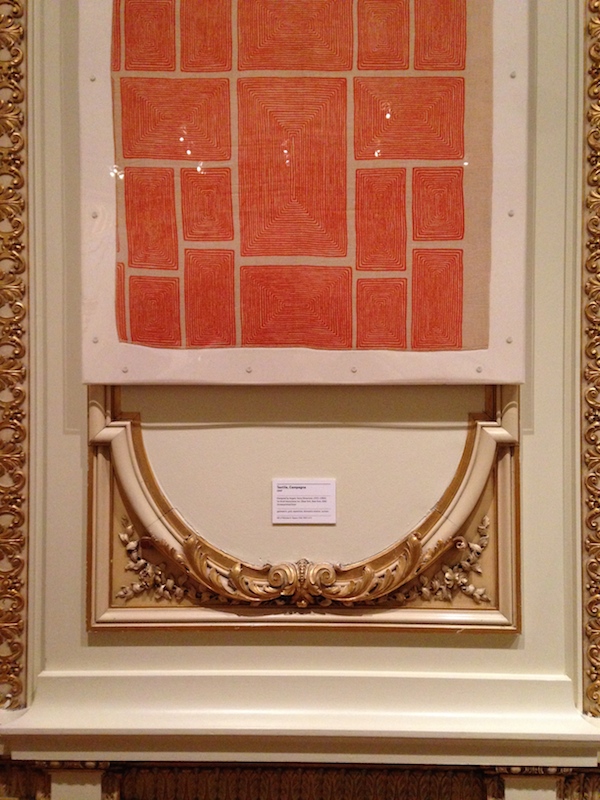

Visit: Cooper Hewitt

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (which has finally cleaned up its name, among many, many other changes) reopens after a three-year “transformation” on Friday, December 12. My review is forthcoming, but one of the things I liked best about the installation of the collection was the many, many different ways they framed design, and design framed itself. These photos show that. If you want more of the architecture, John Hill posted a collection of shots that give an overview. I got distracted by all the shiny objects.

High Designs

Olabuenaga House, 1989-97, in Maui. Photo by Grey Crawford.

What does a computer look like? We recognize them now as slim and metallic, but not so long ago they were bubbly and candy-colored. Before that they were black and boxy. Before that they filled rooms, attended by staff. (Before that, computers were staff.) Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007), the Italian architect, designer and provocateur, was one of the first to grapple with the character of these new objects in the office landscape.

Sottsass was hired by the electronics manufacturer Olivetti in the late 1950s to design the first computer made in Italy, the Elea. For him to succeed, something strange had to be domesticated, or urbanized or organized. It was hard to say which. Olivetti’s electronics division in Pisa “was a world of science fiction, inhabited by engineers in white coats moving among mountains of wires and valves,” in the telling of Sottsass’s biographer (and widow) Barbara Radice. His solution was to treat the mainframe as a city, with aluminum skyscrapers attached to infrastructure in the sky. Those skyscrapers — smooth-sided, wardrobe-size boxes — were scaled to humans, to avoid alienation for their engineers. A grid of color-coded metal channels carried cables and wires overhead, allowing for rearrangement and future growth. With the Elea, Sottsass created just one of his many totems for the modern age, designing bridges between the handmade (or hand-computed) past and the machine-made future.

A new, comprehensive monograph on Sottsass by Philippe Thomé includes all of these totems, from the adorable Valentine typewriter to the suave Alessi fruit bowl, the Meccano-set modernism of the Elea to the color explosion of Memphis.

Visit: Making Music Modern

Jan Lenica. "Wozzeck," 1964. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

The Museum of Modern Art periodically refreshes its permanent collection design galleries. For the past year, the theme was “Designing Modern Women,” in two phases. I wrote about my disquiet with the expanded definition of “women’s work” in the first of those two installations here. On November 15, the museum opened a brand-new installation, Making Music Modern: Design for Ear and Eye that I can recommend without reservation. I’ve written before about my love of themed collection shows: big museums have so many things that never see the light of a gallery, and I’m always excited to see juxtapositions of big names and never-heard-of-hims or -hers, as well as the layering of different media themes can bring. Music, as it happens, is a particularly rich and broad theme.

We have architecture, in the form of a fabulous sketch by German Expressionist architect Hans Poelzig (usually resigned to the quirky margins), an incredible model of the Sydney Opera House that shows where the roof shapes came from (curator Juliet Kinchin said she thought it had never before been exhibited), and a recent model of Snohetta’s Oslo Opera House.

We have posters galore, from Loie Fuller to the Beatles, psychedelia to Paula Scher. I loved the three huge classical music posters from the 1980s, by Croatian designer Boris Bucan, that meet you at the top of the escalator.

Radios, phonographs, speakers and iPods, including Dieter Rams and Hans Gugelot’s “Snow White’s Coffin” SK4/10 for Braun. It’s a lot of things, people, and sounds you wouldn’t usually put together, demonstrating the strengths of MoMA’s collection and also making connections between the past and the present day. Try to go during one of the lunchtime performances of the instruments of the past, and don’t miss the subtle transparent speakers overhead.

Gridded + Starred

Galaxy Wrapping Paper from Norman's Printery

I have a love/hate relationship with Pinterest, but I do love a theme. I’m not posting a Gift Guide, because I’m not a magazine or a style blogger, but I have created boards that are filled with fun things with grids and with stars. Why use galaxy wrapping paper as wrapping paper, for example, when it could be decor? And here’s where to get your “What Would Jane Jacobs Do?” t-shirt.

Open With Care (for Nordic Design)

The success of Birchbox, the monthly beauty sample subscription box, has spawned many emulators. There are subscription boxes for nail polish, for organic snacks, for homemade food and handmade items. What there aren’t many of, Ana Denmark, 32, noticed, was a subscription box for housewares, particularly the clean and simple home goods from Scandinavia that she favors. After checking out dozens of boxes in the name of research, Ms. Denmark launched Skandicrush in August, sending out her first $50 package to subscribers in October. Currently running a one-woman, self-financed business, with inventory stored in her stepson’s bedroom (he’s at college), Ms. Denmark hopes to eventually expand the site into e-commerce, so you can get that butter dish after the box is gone. And she has ideas for some other boxes that don’t involve moisturizers or mixed nuts.

Saving Buildings with Social Media

The gap where the Folk Art Museum used to be, 53rd Street.

In David Macaulay’s illustrated book, “Unbuilding,” published in 1980, a sheikh buys the Empire State Building and has it dismantled, piece by piece, to be reassembled in the Middle East. Macaulay uses this premise—which, when I was seven, seemed like science fiction—to illustrate what goes into unmaking a building: the materials, the methods, the fastenings, the layering. It takes a whole book to take a skyscraper down, and that was part of the point. The slowness of the process, the idea that a building can’t just disappear, was a lesson in itself, and one extraneous to the Empire State Building’s significant particulars. Obviously, post-9/11, the fantasy takes on a different resonance.

Today, we don’t need Macaulay’s detailed illustrations to see buildings being unbuilt. We call it “destructoporn” (since 2007, according to Urban Dictionary) and it comes, unbidden, via digital media. Where did I see that Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s Folk Art Museum, just thirteen years old, was down to steel and rubble? The art critic Jerry Saltz’s Instagram. How did I follow the destruction of Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Women’s Hospital (1975), in Chicago, made of poured-in-place concrete that took weeks to demolish last fall? Tweets from the Windy City’s flock of architecture observers. Twitter also brought me the news, in September, of the unbuilding of John Johansen’s Mechanic Theatre (1967), in Baltimore, and a view of the wrecking ball demolishing a hundred-and-twenty-nine-year-old commercial row in Dallas. Unfortunately, except for the copper-bronze façade of the Folk Art Museum, the parts of these buildings aren’t being shipped anywhere except the landfill. No Middle Eastern resurrection to come. Something glassy instead.

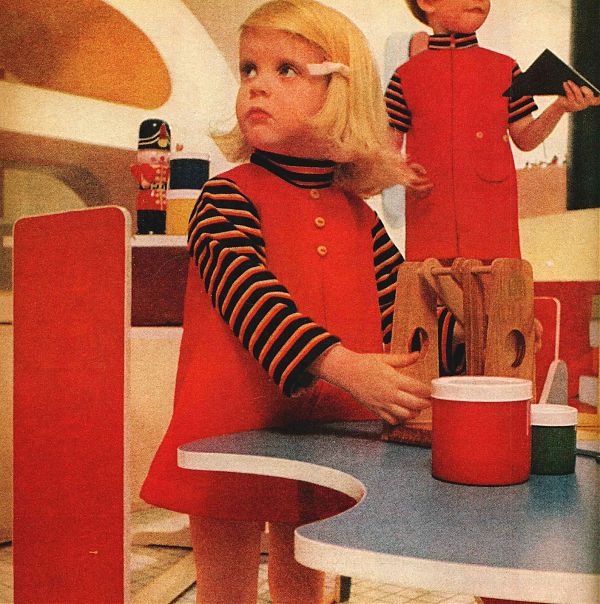

Blue is For Blondes

Parents Magazine, July 1970

Recent research on the history of children and color shows that the gender binary (blue is for boys, pink is for girls) is of postwar vintage. Color has been an indicator, in the pint-sized realm, of so many other things. Age, separating the wardrobe of white-dressed infants from the breeched in colored rompers or knickers. Interests, manifested in wallpapers with transportation scenes or Western stampedes. Program, with bright colors in the playroom and soothing hues in the bedroom. Complexion, red for brunettes and blue for blondes. This essay explores a few of those choices, which overlap and interweave rather than advancing toward a color-coded future.

For Saturated Space, I explore the evolution of American children’s colour-space in the 20th century.

"History does change perception."

In the centre of the first wall of chronology in the new exhibition Michael Graves: Past as Prologue is a little shelf. On that shelf rests a cookie tin decorated to look like his Portland Building (1982). The proportions seem a little off, since the tin is taller than it is wide. In my mind, the Portland Building is a perfect cube, closer to its foreshortened appearance from the sidewalk, and closer to the penciled yellow-trace drawings of facades that were my first introduction to Graves’s work.

In my memory these facade drawings are all squares, made up of triangles and half-rounds, chunky columns and square windows, ideal for transformation into an animated gif of architectural design as an exercise in two-dimensional composition. When Graves took on the Whitney Museum, in 1985, he tried to make Marcel Breuer’s facade into one of those bits, stubbornly stuck in the lower left-hand corner of his pile. But Breuer’s building resists the cookie tin. It would probably tip over. It would look dull on a shelf. While Graves suggests biscotti, Breuer doesn’t seem like a sweet.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness