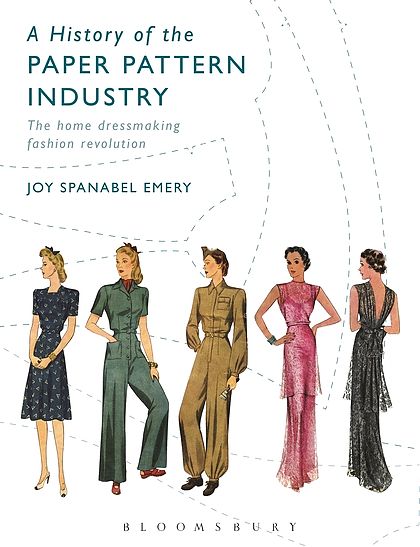

Review: A History of the Paper Pattern Industry

The Commercial Pattern Archive, located at the University of Rhode Island, is a wondrous thing, a visual chronicle not only of the vicissitudes of sewing over the past century and a half, but also a window into home technology, fashion, and the rights and roles of women. A History of the Paper Pattern Industry by Joy Spanabel Emery, the archives’ curator, wends its way through that chronicle’s highlights, offering illustrative examples of the way patterns reflect media, love and war. It’s an academic book, alternately dry and fascinating, so I offer highlights by way of review. I hope others, inspired by this beginning, will take it and run in different interpretive directions, as I did with the 3D printer. Apologies for the home-sewn photography.

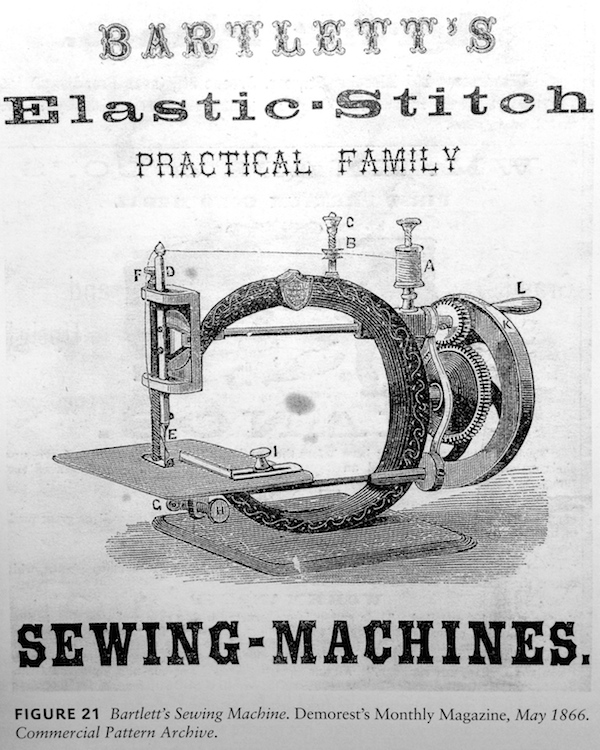

The first home sewing machine was designed in 1856, and cost $125 ($2,997 in 2010 or, about the cost of a 3D printer today). To offset the cost for individuals, Godey’s Lady’s Book suggested that families pool their resources and buy one together (like Techshop for the rural village); others offered rent-to-own plans, $5 down and the rest to be paid with interest.

Women took to the new machines faster than their male, professional colleagues. This caused concern not only that home sewing might put tailors out of business, but also that it might make women’s lives too easy. Betty Williams noted, “many men wanted to believe that women couldn’t handle such a complicated piece of machinery; they feared that if women did perform their sewing duties in less time there would be time left over for them to improve themselves or participate in the suffrage movement.”

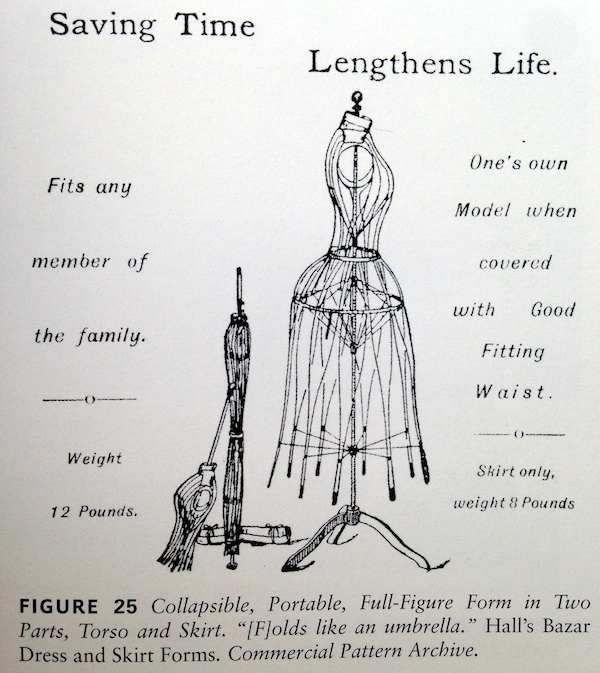

Sewing machines were not the only technology that needed improvement: the dress form was also the subject of design innovation and experiment. Hall’s Bazar Form Company adapted the idea of the umbrella, with metal ribs that can be collapsed or expanded, into a two-part form (torso and skirt) that could be collapsed into a column for storage.

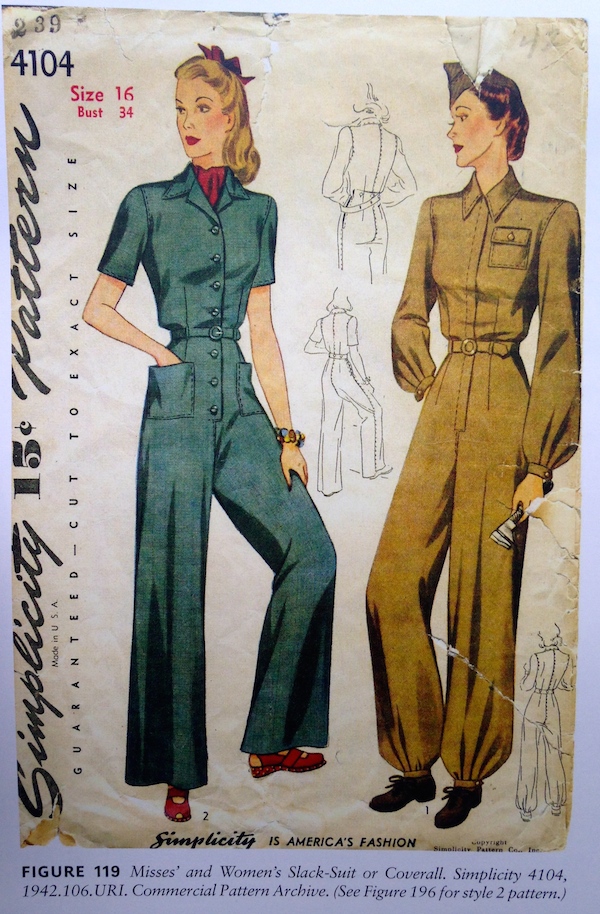

The first World War affected the pattern industry in a number of ways. “The Dress of Patriotism,” published by McCall in 1918, was advertised as requiring only two yards of 54-inch material, saving wool for “over there.” McCall also published a pattern for a ladies’ work suit, as recommended for women in the cavalry corps or defense plants. Other companies created patterns for Red Cross nurse uniforms, as well as operating masks, gowns and hospital robes to be sewn and donated to hospitals.

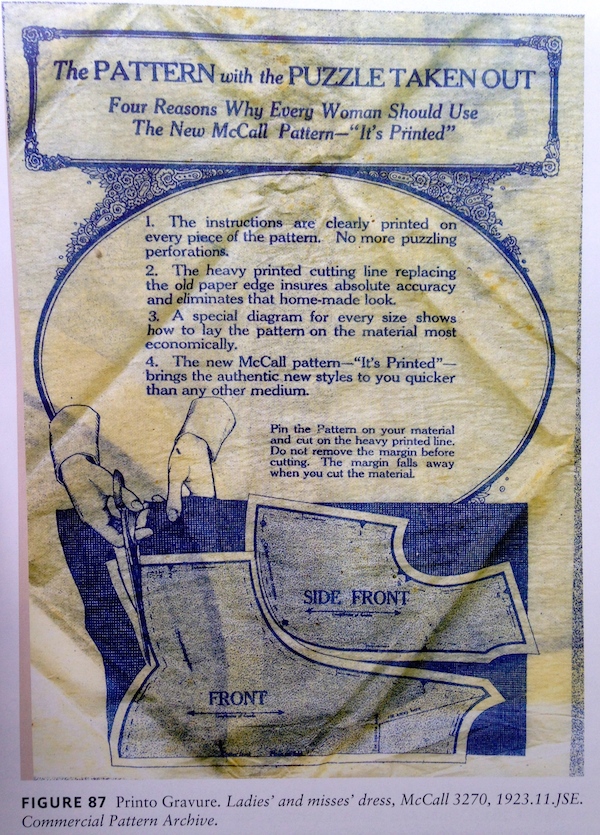

Before 1920, commercial patterns had been machine cut and punched, and home sewers had to learn a common language of punched holes corresponding to different cuts, pleats, and other moves. The McCall Printed Pattern was announced in 1921 as “the biggest invention since the sewing machine.” Pattern pieces were printed in outline, along with all other markings indicating darts, alignment, and the name of each section. The McCall tagline, “It’s printed,” recalls Lucky Strike’s, “It’s toasted,” as a minimalist indicator of a serious difference. McCall rivals came up with ways around their patent; Pictorial Review wrote that the new pattern markings were so clear it “ALMOST TALKS TO YOU and answers all your questions satisfactorily and promptly.”

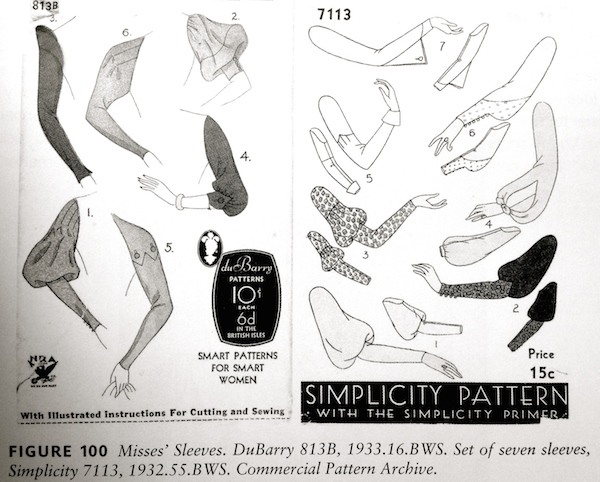

During the Depression, women tried to reuse patterns and recycle clothing, leading to an alternative market for refresher pieces like sleeves, collars and cuffs. I love the abstraction of these covers from DuBarry, which suggest the limited range of our current sleeve choices.

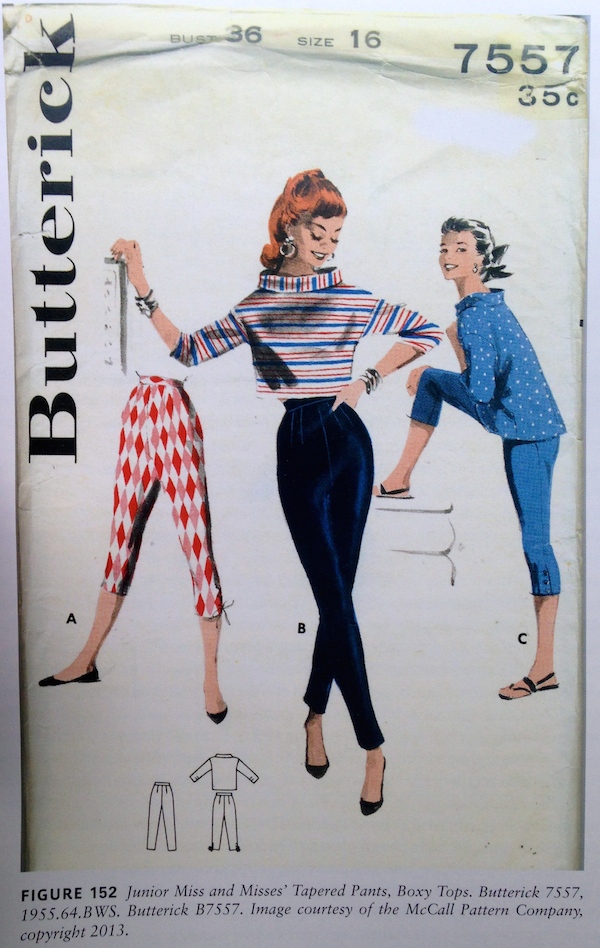

Emery writes, “a common misconception is that by the 1960s women stopped sewing and making their own clothes due to the mass of inexpensive, readily available ready-to-wear options. However, the 1960s were actually a boom period.” Celebrity endorsements, TV advertising and educational programming, plus manufacturer-sponsored sewing classes in schools all contributed to a 40M individual market, averaging 27 garments per person per year. Four out of five teenage girls made their own clothes. “The summer 1967 issue of American Fabrics stressed the growing appeal of sewing to express individuality and as a mark of elegant economy.”

Trends of the past, as interpreted through paper patterns. The minidress.

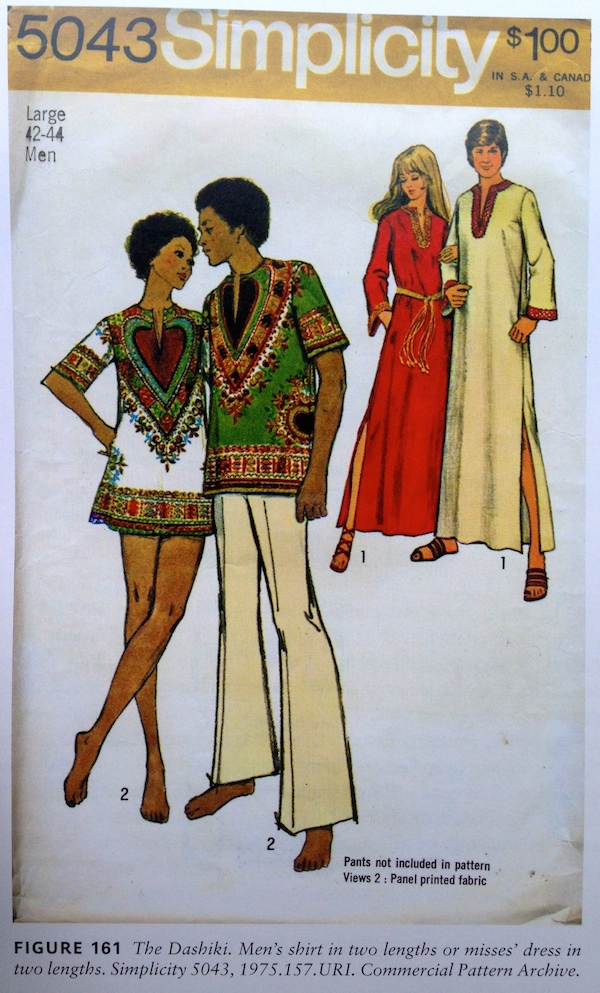

The dashiki.

Dynasty.

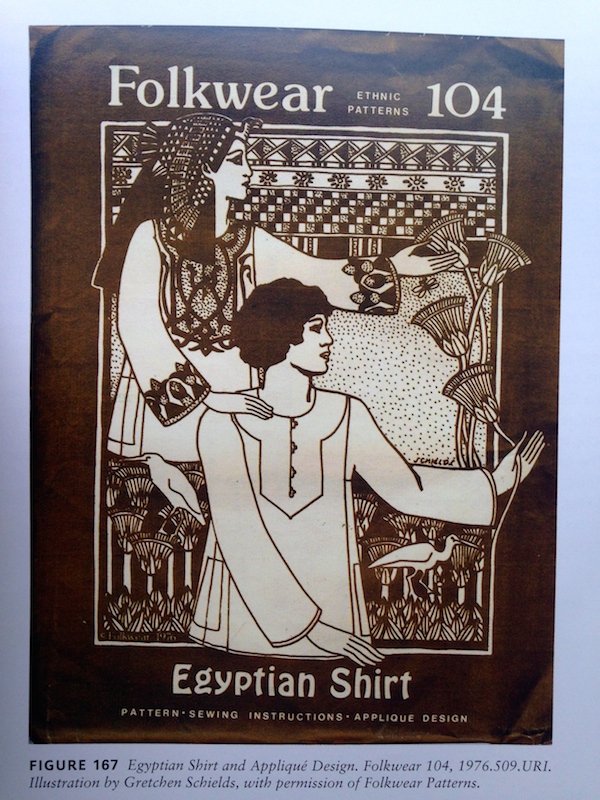

By the 1980s, home sewing was shrinking. And yet the history ends on a hopeful note, with a smaller, more focused revival of interest spurred by the combination of digital technology and the sewing machine, through automation, apps, and embroidery at the push of a button. Pattern design focused on parts of the market not served by ready-made clothing, like traditional clothing, historic recreations, and children’s gear. The appendix to Emery’s book offers reconstructed patterns first issued from 1850 to 1960, should you want a pointed basque, a drop-waist 1929 sheath, or a Nehru jacket. Project Runway didn’t hurt either. Digital forums provide the modern-day equivalent of the sewing circle, offering ideas, encouragement and trouble-shooting even when one is sewing alone.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness