Decoder Ring: The Mystery of the Sandbox

I’m on the Slate Decoder Ring podcast this week discussing the play equipment that started a movement: The sandbox!

The Good, the Bad, and the Overbuilt: 2025 Architecture & Design Awards

Back for the 16th (!) consecutive year with the totally prestigious, totally made-up Architecture & Design Awards, co-written with Mark Lamster and Carolina Miranda.

But in keeping with the times (and because we are lazy), we’ve decided to leave the writing of the introduction to ChatGPT:

Architecture in 2025 reflects a discipline reshaped by urgent environmental demands, rapid technological advances, and a renewed commitment to social purpose. The most distinguished work of the year demonstrates how design can respond creatively to these pressures — balancing innovation with responsibility, beauty with equity, and experimentation with a deep respect for place. This year’s awards highlight projects that rethink the limits of material efficiency, expand models for sustainable and affordable housing, and elevate community voices in the design process. They also celebrate adaptive reuse efforts that preserve cultural memory while charting new futures for existing structures. Together, these honors offer a snapshot of a field in motion, recognizing architects whose work helps define what meaningful, forward-looking design can be today.

How inspiring. And now on to the fake awards. Enjoy!

Culture Study Q&A: The Design of Childhood

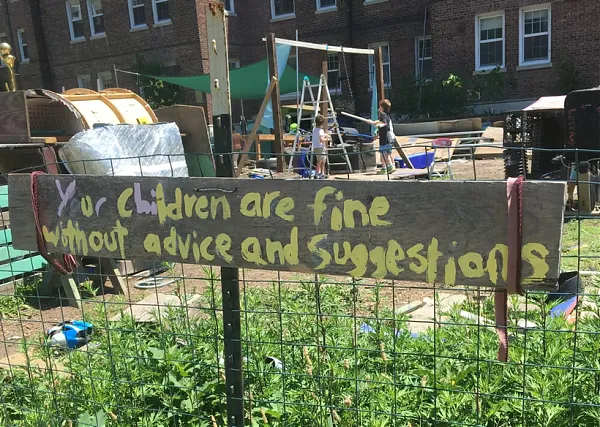

The key sign at The Yard on Governors Island.

Thank you to Anne Helen Petersen for this long interview for the reissue of the childhood book! We discuss courtyards, Nugget couches, Unit blocks, junk playgrounds, car-free politics and much more.

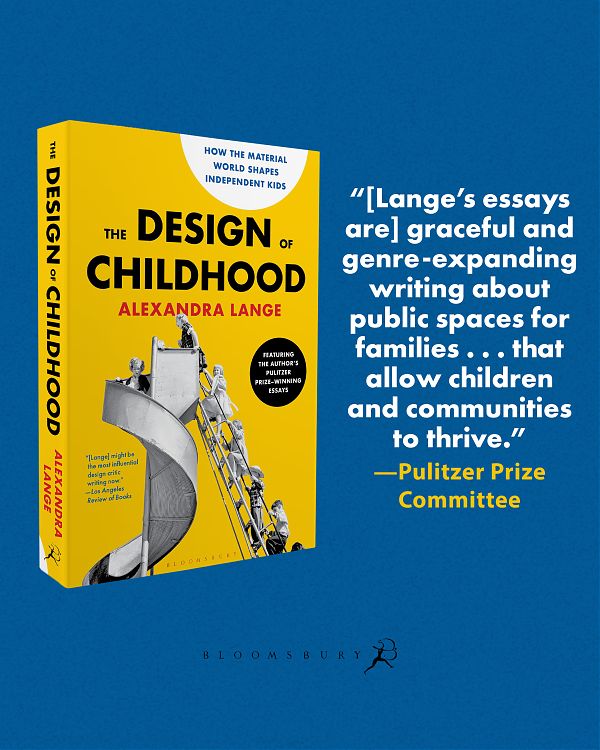

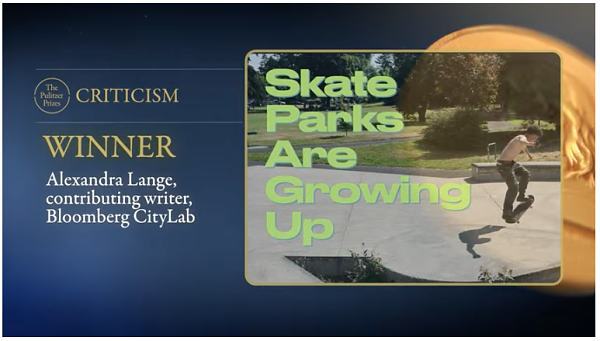

Now, let’s talk about THE DESIGN OF CHILDHOOD. Alexandra Lange is one of those of people you started following on Instagram a billion years ago, have no memory of how it happened, but now you’re like: this person has forever changed my thinking. Most concretely through her books (Meet Me by the Fountain and The Design of Childhood, the topic of our conversation below) but also through her columns (most recently at Bloomberg CityLab — which earned her the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in Criticism) and her IG stories, which expose me to architectural wonders (obvious and mundane) on a daily basis.

99PI: U Is for Urbanism

I’m back on 99 Percent Invisible talking about the Pulitzer and design for teens, at the end of an episode devoted to Sesame Street and urbanism.

Finnish-Style Baby Boxes Get a New York Twist

Two weeks before his election as mayor, Zohran Mamdani held about the cutest press conference you can imagine: Surrounded by babies, and backed by a blue climbing structure, he announced that he would launch citywide “baby baskets,” welcoming the 125,000 babies born in New York City each year with a free collection of essential supplies. Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, who sponsored a pilot program of 500 “Born in Brooklyn” baby boxes in 2022, introduced Mamdani, saying, “This is a sacred act to have a baby … We want to make sure the last thing you are thinking about is a box of diapers.”

Left unmentioned was the fact that, just a week earlier, Mamdani’s onetime opponent, sitting Mayor Eric Adams, had launched his own baby box program at four of the city’s public hospitals — two in the Bronx, one in Brooklyn, and one in Queens — where more than 7,000 babies are delivered each year. The cost of the NYC Health + Hospitals program is $2.6 million for year one, funded through city tax dollars. The boxes themselves are provided by Welcome Baby USA, a nonprofit organization founded by Sarah Gould Steinhardt in 2019 that had already been providing a smaller number of care packages to Jacobi Medical Center, one of the Bronx launch sites.

The Design of Childhood returns

Today’s the day: Welcome to the expanded paperback of The Design of Childhood featuring a new introduction and all seven of my Pulitzer Prize-winning essays. Plus, for the first time, an audiobook!

Alexandra Lange on Shade

An urgent civic need, too long in the shadows

Three Julys ago I was in Rome with my family. Late afternoon, exiting the Forum, trying to cross the street, I felt like I had been struck blind. Some combination of the strength of the summer sun, its low angle, and the stone surfaces around us meant that, despite my sunglasses, it felt as if my eyes were being pierced by hundreds of daggers. I stumbled over to a wall and tried to explain to my family members that I could not see. They would either have to guide me or leave me there until the sun went down. We waited until the earth rotated just a few more degrees, but I remembered that moment reading Shade: The Promise of a Forgotten Natural Resource. “In ancient Rome,” writes environmental journalist Sam Bloch, “the porticoes formed a shadow network that stretched for two miles, and a fully covered walk to the Roman Forum struck visitors with wonder. One could effectively stroll from one side of the ancient city to the other in shade.” As the world warms, many have no choice but to work or commute in the heat of the day. The ancients had us (literally) covered.

Bloch’s book, which moves through the past, present, and future of shade from a variety of angles, is filled with such invitations to see the built environment afresh. It’s a bit like a figure-ground puzzle: Are you looking at the black or the white? Shadow or sun?

Not Only Survive, but Flourish: The Story of WSPA

WSPA 1975. (Courtesy Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College)

Our latest episode of the New Angle: Voice podcast describes the creation and experience of the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture, popularly known as WSPA, which ran for four summers from 1974 to 1979. It completes a trilogy of episodes, including previous ones on the fantasy environments of architect Phyllis Birkby and the first exhibition on Women in American Architecture at the Brooklyn Museum, that ask and answer the question, How did architecture meet the feminist movement in the 1970s?

WSPA was the brainchild of seven women, Leslie Kanes Weisman, Phyllis Birkby, Katrin Adam, Bobbie Sue Hood, Ellen Perry Berkeley, Marie Kennedy, and Joan Forrester Sprague. These women represented a mix of academic, professional, and practical experience. What they wanted to create was an educational curriculum, by women and for women, that freed architecture from the hierarchies of existing schools and practice.

Winner of the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in Criticism

For this series on designing better public space for children and families.

Thank you to the Pulitzer Prize jury for this award, and to my editors at Bloomberg CityLab, Kriston Capps, Nicole Flatow, and David Dudley, for encouraging and supporting this work. Kids deserve the best.

Inside Richard Neutra’s 1949 Wirin House

Photograph by Chris Mottalini

Home improvement books often start with a caveat: “Don’t make big changes until you’ve lived in the house.” When the home is a midcentury gem by the legendary modernist Richard Neutra, that advice comes with teeth. “We have to be very careful,” says Alberto Chehebar of his residence, the 1949 Wirin House in Los Feliz, California.

His wife Jocelyne Katz puts it more bluntly: “The house owns us.” This sense of stewardship has been deepened by the recent fires in Los Angeles; many of the city’s other houses, threatened or lost, were built on similar hillside sites.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness