How To Unforget

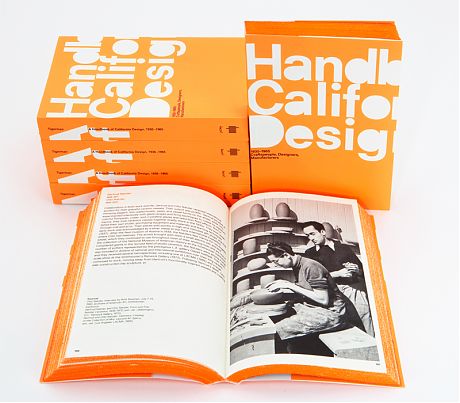

A Handbook of California Design, 1930-1965: Craftspeople, Designers, Manufacturers (Los Angeles County Museum of Art and MIT Press), edited by Bobbye Tigerman (via LAMA)

A few weeks ago Despina Stratigakos published a vigorous call to arms for historians at Places, “Unforgetting Women Architects: From the Pritzker to Wikipedia.“ She writes,

History is not a simple meritocracy: it is a narrative of the past written and revised — or not written at all — by people with agendas. Forgetting women architects has also been imbedded in the very models we use for writing architectural history. The monograph format, which has long dominated the field, lends itself to the celebration of the heroic “genius,” typically a male figure defined by qualities such as boldness, independence, toughness and vigor — all of which have been coded in Western culture as masculine traits. Moreover, the monograph is usually conceived as a sort of genealogy, which places the architect in a lineage of “great men,” laying out both the “masters” from whom he has descended and the impressive followers in his wake. For those seeking to write other kinds of narratives, the monograph has felt like an intellectual straitjacket, especially in contemplating the lives and careers of women who do not fit the prescribed contours.

Stratigakos’s essay serves as a digital call to arms, to get more women into Wikipedia and other online encyclopedias so that (at minimum) their existance cannot be called into question. But digital means are not the only ways of unforgetting, and when I finally picked up the neon orange A Handbook of California Design, 1930-1965: Craftspeople, Designers, Manufacturers, published this spring as a companion and follow-on to the 2012 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Living In A Modern Way,” it seemed like another means of unforgetting, one which takes on the monograph form by suggesting that a group biography, emphasizing connections, collaborations and a sort of collective design advancement, might do just as well.

The book, edited by curator Bobbye Tigerman and designed with her usual aggressive simplicity by Irma Boom, includes 140 one-page biographies of what Tigerman calls “significant figures from the period 1930 to 1965 and the full range of design disciplines.” Each entry is illustrated, usually with a period portrait, and each includes a short bibliography of sources. Each could, and in most cases should, be a jumping off point for a longer work, whether a Wikipedia entry, an essay, or an old-fashioned monograph. Those modest, helpful notes are a rebuke to so many contemporary design books that think they can do without a bibliography. Even better would be an online database of these articles (even if it had to be protected in some way), sharing the PDF wealth and making the first research step that much easier. If architecture history has been slow to recognize other types of careers in book form, design has been slower still. The textile designers represented here alone deserve so much more study, from the new fibers in bathing suits, to “first lady of the loom” Dorothy Liebes, to Lanette Scheeline‘s pictorial screenprints.

Obviously a number of the names I just mentioned are those of women. By framing their compendium as on “craftspeople, designers, manufacturers” the museum also easily includes a large percentage of women, working across the design fields, both in partnerships and alone. Ray Eames, the best known of these female California designers, was not as exceptional as we might have initially thought, though her work always will be. I only recently found out about Victor Gruen’s wide, Elsie Krummeck Crawford, who worked with Gruen on iconic retail projects like Joseph Magnin and Barton’s Bonbonniere, and later designed public sculpture, textiles, toys and seating planters for Architectural Fiberglass. Marget Larsen, another name new to me, also did some amazing advertising and supergraphic work. It isn’t just the women, either, that broaden the range of design histories included here. There is a biography of Marion Sampler, the longtime head of the graphics department at Victor Gruen Associates, who happens to have been African American. And one for Carlos Diniz, an architectural delineator who may actually be the reason we remember work by Gruen, Yamasaki, Gehry, SOM, and many others. (I will admit, I have never made deep study of California design, and some of these names and facts will be better known to others.)

Many of the designers and craftspeople mentioned in the Handbook were familiar to me through commerce rather than study. Everyone knows, and hence knows the price of, work by the Eameses. But Kenji Fujita, La Gardo Tackett and Architectural Pottery, Jade Snow Wong, were only known to me because I follow the hashtag #thriftbreak on Twitter. I’ve written about this virtual community before, as I am continuously impressed by their ability to pick museum-quality modernism out of the HomeGoods detritus of Goodwills, Savers, and tag sales. They know about these lesser-known talents because pieces and sets are still out there for the picking, particularly on the West Coast. While many on #thriftbreak will surely want to buy this book, they may be graitified to hear that most of the listed artists are illustrated by portraits. Finding all of those portraits is an accomplishment — Tigerman offers special thanks to the photo research of Staci Steinberger in her acknolwedgements — but it would have been nice to have images of the products alongside some of the portraits. After a while I began Googling each person whose biography interested me, to see whether what they made was as intriguing.

I also occasionally questioned the book’s broad definition of California-ness. Herbert Matter, for example, is hardly a forgotten designer (the bibliography mentions both a documentary and a monograph), and spent only three years in California, from 1943 to 1946, working for the Eames Office. I understand his usefulness here as a collaborator on the graphic and photographic presentation of the Eameses’ work, as well as design for Arts and Architecture magazine, but did California change his career? Did he change its design? It seems more like an interlude before he took his angles and abstraction back to New York in the service of Knoll, Inc. More productive is seeing figures like industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, whom I’ve always identified with New York, in a West Coast setting. Dreyfuss set up an office in Pasadena in 1944, and was officially a California resident after 1945. Many of the Dreyfuss office’s most important clients, including John Deere, Polaroid and Lockheed were served by partners based in Pasadena. The geographic displacement made me think about more local connections, like that of car design, Pasadena, and Art Center. Dreyfuss employee Strother MacMinn, who gets his own entry, began teaching at Art Center in the 1940s. “At the time of MacMinn’s death, his eulogist estimated that one-third of all important American automotive designers had trained with him,” Steinberger writes.

Another unexpected inclusion is that of fashion designers and manufacturers. I didn’t get to see “Living In A Modern Way“ when it was up at LACMA, so I can’t judge how companies like Cole of California, Catalina Sportswear were integrated into the overall exhibition narrative. I can see the visual link between the bikini, as shown above, like Architectural Pottery’s outdoor planter, as an embodiment of the lifestyle sandwiched between the sliding glass door and tiled pool of the mid-century Californian architect. The advertisement above, reprinted in the book, also makes a connection between the revolutionary new textiles and the streamlined products abundant on store shelves in the 1940s. Maybe I’m talking myself into it, but it seems telling that these fashion companies are not shown on the (almost illegible) chart of “Connections and Collaborators” at the front of the book. They seem to exist in their own, separate-but-connected world.

But these are small points. Overall, the Handbook is a must-buy for those interested in mid-century design, and a model of the kind of scholarship and publishing that leads to less forgetting, and more knowledge, of the accomplishments of all kinds of designers.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness