Review: Alexandra Lange on Danish Modern

My childhood best friend’s dining room hosted a suite of matching wood furniture: a tall glass-fronted sideboard; a table that stored its extra leaves below the surface, to be pulled out like drawers; chairs with open backs and black leather seats, all in a mellow amber tone. As she moved across the country, and up the West Coast, a coffee table moved with her, worth the trouble because, from the eighties to the aughts to the 2020s, it remained in style, as suited to a brick Colonial Revival home in Durham as it was to a PNW Craftsman.

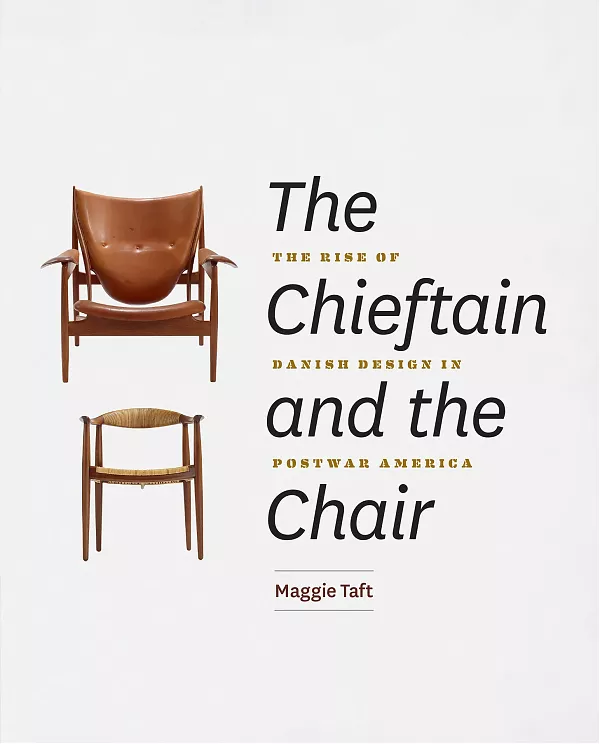

This was intentional: From the moment such furniture appeared on American shores in the 1950s it was advertised as “address[ing] the needs of younger couples and new households, with its cleanliness of design.” Its “soft, rounded flowing forms” evoked the craftsmanship of an earlier era, while its “tapered lines” indicated to the world that you weren’t stuck in the past. While the style first drew attention in 1949 with a pair of chairs—the Chieftain, by Danish architect Finn Juhl, and the Round Chair, by Danish furniture designer Hans Wegner—when American manufacturers got done with it, you could buy a recliner, a stereo, a television, in still-desirable, still-salable Danish Modern. The authorship and by and large the artistry of the original chairs was effaced by the wave of cheaper, mass-produced copies, many of them made by American manufacturers, for American homes, with only the lightest sprinkling of Danish-ness.

In her new book The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America, Maggie Taft sets out to tell the story of how we got from the 1949 Cabinetmakers Guild Exhibition in Copenhagen, where Juhl showed his chair, with its shield-shaped back, next to a pinboard of influences including a bow and a photograph of an African hunter with spear (Juhl’s “romantic—and colonizing—view of primitive authenticity”) to the handsome, if slightly generic, coffee table in my friend’s living room.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness